I came to the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis with all the quotes playing in my head, quotes I could now recite by heart, ideals I had learned to embrace: That we will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.

That we must judge people not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

That injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

Sr. Joan Byrne, hosting me for a week’s break in the city where she has worked for 45 years, had dropped me off in the back parking lot of the museum on a damp Tuesday morning. It was quite a new concrete building, housing “an immersive experience” according to the guidebook. I walked up a slight incline and round the corner, to arrive at — the motel where Martin Luther King had been assassinated.

For a second I felt dread and nausea, even fear.

The 1968 photo was etched in my mind: Andrew Young, Ralph Abernathy and others pointing across to where the gunman had stood, the renowned civil rights leader dying on the ground in front of them, at 39 years old.

King would have been 95 on his January birthday this year — now a national holiday. His memorial day brings many of us a mixture of admiration and sorrow, not just because his life was so short but because, for a large part, his dream has not been fulfilled.

Sure, Black Americans are among the most celebrated actors, sports people and musicians of our time; and they are not at all confined to these fields for their successes. Their range of occupations is about the same as that of the white labour force. They are doctors, lawyers, businessmen, clergy, film directors, Supreme Court Justices, and recently, a US President. (Black Demographics, 2017).

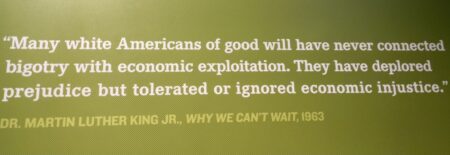

However, they are twice as likely as white people to work in lower-echelon jobs, and their unemployment rate is almost double that of the white population (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017). All carry with them a huge burden of the past, a past which had them shackled, owned, valued at three-fifths of a human being. Poverty still dogs those who live in the cities, where substandard housing, overcrowding, and lack of jobs almost guarantee unstable family life, evictions, violence, mental and physical health problems. They live, in the words of Dr. King, “on the lonely island of poverty in the middle of a vast ocean of prosperity.” Just before the pandemic, the white poverty rate was 9 percent, but the black poverty rate was 21 percent. (Current Affairs, September 2022). Yet, as in many of the immigrant ghettos of previous centuries, there’s a strong sense of community among black people, and they build community, drawing strength from each other.

Inner-city schools are underfunded and suffer from staff burnout and staff turnover: this means that the one potential avenue of escape from poverty, an education, is simply not as available to the urban poor as it is to the middle-class.

Activist and educator Jonathan Kozol calls this “apartheid schooling.” Urban students of color continue to face derelict buildings, fewer choices, and from their teachers, lower expectations. When he asked children to write about their schools, one 8-year-old from the Bronx wrote asking for play spaces and bathrooms. “We do not have the things you have” the child said. “You have Clean things.” (NCRM 2013).

Because of inexperienced teachers and of students’ own life traumas, discipline can be an issue, one that is often poorly handled. In some inner-city schools, infractions are dealt with severely, even criminalized: in Georgia, for example, “disruption”— which can mean something as simple as back-talk—is reported to the police, so that even though students are not jailed for such offences, their records show the unjustified category of criminal behaviour. This impedes progress through future schooling (Learning for Justice, Fall 2022). Worse, it can result in lengthy suspensions from school, leaving the students at the mercy of the streets.

As I walked around the Civil Rights Museum reading the walls and watching videos, I was gripped not only by the imaginative and vivid displays on disparities in education, but also by the biographies of great black educators, pioneers and innovators when segregation was either the law or the practice: Mary McLeod Bethune, Charlotte Perkins Brown, Kelly Miller, Dr. Edmund Gordon, and many others. Mary McLeod Bethune, for example, established a girls’ school in Florida in 1904; her mission in life was to provide quality education for young black women, and thus promote political power for all. Recognized for her work, she became part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet.” Edmund Gordon was a founder of Head Start, a government program providing free learning and development services for children in low-income families, from birth to five years old.

I also thought with pride about how our Catholic schools in the USA have a history of educating poor children, providing stable environments where children from every background and racial group were valued, challenged, and encouraged. Sadly, nowadays it is increasingly difficult to provide low-cost education outside the government system, as Sisters of active apostolic orders have gradually retired from teaching, and our former schools, when not completely closed, are in the hands of teachers raising families, who naturally need a full salary.

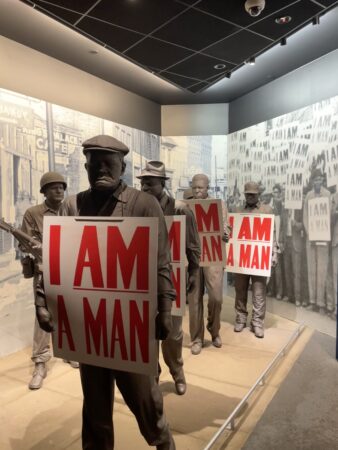

After the education section, I stopped longest by the life-size figures of courageous women and men, ordinary people challenging the status quo: the housekeepers and factory hands who trudged miles to work rather than take the segregated buses in the 1960s Mongomery Bus Boycott. The striking sanitation workers bearing placards announcing “I Am A Man” after two of their number were crushed in the rear of a garbage truck in February 1968. Thirteen hundred of them came out on strike, determined to stay off the job until they received a decent living wage and safe working conditions. They wanted their humanity and dignity recognized.

I cannot fathom the courage – and the pain – it took before a person could take up that placard and proclaim he was a human being.

It was in support of these workers that Rev. King came to Memphis in March and April 1968. And it was here he met his death.

His last speech, given in a Memphis church on April 3rd, was powerfully prophetic in its evocation of Moses in sight of the promised land, to which he had led his people, but never entered.

Dr. King came from a preaching tradition – his father was a pastor before him – and he lived the struggle for justice as a call from God. His most powerful metaphors were biblically based. The biblical scenes and language were simply part of the furniture of his mind. That night in Memphis he quoted the prophet Amos, “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” He finished his sermon: “I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop, and I don’t mind.”

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life… But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will, and He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the Promised Land!”

I read about the atmosphere in that church as he finished this sermon — it was electric. “As King collapsed into his chair, the crowd rose up from theirs, roaring and clapping. Historian Joan Beifuss later described the crowd as ‘caught between tears and applause.’ Even among the ministers in the auditorium who knew King’s oratory well, the emotional charge of his words provoked shivers.” (Rosenbloom, 2018)

Then he was dead, at 39.

The work of this remarkable man, a leader in the struggle for social justice, is still so important for us to think about in this Black History Month, February 2024. We honor him this month, along with Medgar and Myrlie Evers, Ralph Abernathy, Fannie Lou Hamer, Bayard Rustin, Rosa Parks, John Lewis, and others, whether they were front and center or working behind the lines; not only honor but learn from them how to continue that work.

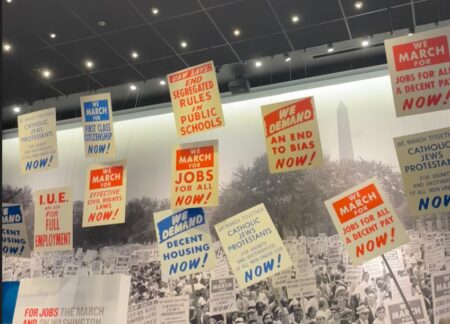

In 1963, Dr. King had given his landmark speech, “I Have a Dream” before 200,000, during The March to Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Now, so many years after his vision of the Promised Land of justice for all, we know it takes ongoing work to overcome a long history of injustice, to keep establishing equality and justice for all.

Worldwide, the gap between rich and poor keeps widening. Millions of displaced people wander the globe in search of a stable home, and the terrible damages of war dominate the news. Immigrants, and any people different from the mainstream, are regarded with fear and suspicion.

We have to put on our awareness specs regularly and notice the inequality gap.

I have to wake up to the fact that it is the “outsiders,” however the dominant class identifies them, who suffer most in that gap. I have to acknowledge the existence of Structural Racism, a complex, interconnected system, in which I am a participant, like it or not. I’ve become so used to the advantages I enjoy as a member of the dominant racial group, that I can’t see them anymore. And because of the many ways I use the system, I am part of what keeps it going. That is frightening to think of.

How can I work to change it in any way? President Barack Obama, talking to a graduating class at Howard University, a historically Black college, told them:

“To bring about structural change, lasting change, awareness is not enough. It requires changes in law, changes in custom. If you care about mass incarceration, let me ask you: How are you pressuring members of Congress to pass the criminal justice reform bill now pending before them? If you care about better policing, do you know who your district attorney is? Do you know who appoints the police chief and who writes the police training manual? Find out who they are, what their responsibilities are… [and] hold them accountable if they do not deliver.

Passion is vital, but you’ve got to have a strategy.”

It was coming up to closing time. Finally, the path through the museum had led me to the place of assassination. I could choose to gaze into the very motel bedrooms used by King and staff, and stare out at the balcony they opened onto.

There, I joined a young mother and her two pre-teen children, who hung around looking a bit numb, while she stood silent, tears running down her cheeks.

I thought: But she wasn’t even born, the time he was killed. And yet look how she is hurting.

Me, I had just come to America from Ireland in 1965; I was 20, I knew nothing. Excited by the questioning spirit of the times, with its deeper engagement in social and political life, seen even in the Church, I was initially wary of all the headliners on the community room TV: Rev. King, Malcolm X, Mario Savio, Timothy Leary, and other rabble rousers and rule-breakers who would further upend a precarious stability! Which were the good guys?

But by 1968 I had listened to Martin many times over and heard him; enough to feel intense shock and loss at his death. He had taught us all. “If we are to have peace on earth, our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation; we must develop a world perspective.”

“Forgiveness is not an occasional act. It is a permanent attitude.”

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”

“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

He had come to this wisdom out of a life not of privilege or power, but of struggle and study, learning from world leaders in peace and justice. Out of “a mountain of despair” he had “carved a stone of hope.”

And as I stood with this black woman taking in the history, her history, on which he had made his mark, all I could say to him was Thank you. Thank you for your life.

Mary O’Connor

US Region