Jesuit Fr. Bernard Lonergan once described mystery as the “known unknown.” It wasn’t until I had gone halfway around the world that I realized what this phrase means — when I left Mercy life in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1984 to minister with Sisters of Mercy in South Africa for one or two years.

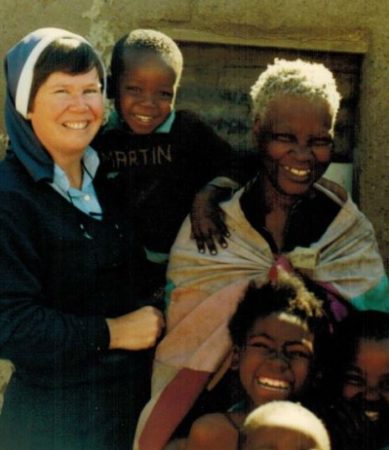

Mercy Sister Jean Evans with a village family

Mercy Sister Jean Evans with a village family

It was exciting to be volunteering in sub-Saharan Africa, but it was also a little frightening because I had no idea what life would really be like there. Well into my second flight from New York to London, I began to realize that going so far away was a little like dying. I was leaving behind all that I knew.

Having cried for nearly half of my 22-hour flight, I freshened up with a not-quite-hot shower in the airport of Nairobi, Kenya. Four hours later, I was met at the Johannesburg airport in South Africa by five Sisters of Mercy. They recognized me!

After a sandwich at the airport (which was pretty much whites-only, as had been my companions on the flight from London), we proceeded to the mission, another few hours’ drive. We passed through Pretoria on our way — the streets littered with the purple flowers of the jacaranda trees. What paradise was I coming to?

When I arrived in South Africa in October, it was nearly the end of the school term before summer vacation in December, in the Southern Hemisphere. I had come to South Africa for several reasons, but mainly because of my experience that God was feeling deep sadness for the people suffering under apartheid; maybe by going to South Africa, I could be of some help.

In 1981, my friend Sr. Judy Carle had attended an international meeting of Sisters of Mercy in Ireland. At that meeting, each group gave a presentation on how Mercy was being lived in their own country. Judy told me the presentation by the South African Sisters impressed her. It was not slick, not high-tech, not even slides: simply a description of the suffering and degradation that the majority of the population was forced to endure because of unjust government policies. The Sisters talked about their work in education — schools open to youngsters of all races — and other ministries of visiting hospitals and prisons, animating Legions of Mary, or running adult education programs after-hours for black South African adults with little or no formal education.

I still remember Judy’s description. She was so animated! There was something so true and so engaging in the presentation of the South African Mercies. I listened, prayed and went to see my superiors. The Sisters of Mercy in Burlingame, California, allowed me to volunteer for one or two years.

Driving west beyond Pretoria’s city streets and the leafy suburbs, we saw miles of dry grass, thorn trees and cactus where herds of cattle grazed in the sun.

Miles later and a quick right turn off the two-lane highway, I saw a sign by the railway line that read “Grens,” an Afrikaans word for “border.” We were heading into another country! It was called “Bophuthatswana” meaning “collection of Tswanas.” I would be living in one of South Africa’s homelands set up by the all-white government to give ersatz citizenship to black South Africans.

Within a few minutes we started passing local landmarks: Motsepe’s Restaurant, a local grocer-cum-liquor store, and next to it a half-completed cinema with steel beams and brick walls awaiting a roof. For the last few miles, we navigated through boulders and rocks, slowing to spare our van’s axles.

Coming into the village of Mmakau, there were corrugated iron “zinc houses” and one or two farmhouses from earlier times. We passed children walking along, old women pushing wheel barrows with 20-litre plastic drums of water, and an occasional donkey grazing along the dusty roadway.

As we pulled into the driveway for the Catholic mission, passed the stone church and climbed the hill, we were met by more jacaranda trees, their purple highlighted by bushes of scarlet bougainvillea around a grotto of Our Lady. What paradise was I coming to?

The Mercy convent in Mmakau

The Mercy convent in Mmakau

Almost ceremonially, I was embraced, hugged, squeezed and welcomed by each of the eight sisters. Entering the house, I saw a table set for lunch, with rolls, a bowl of potato salad, sliced chicken, potato chips and Coke. An old St. Bernard snored away in the corner.

I decided, “This is going to be OK,” and relaxed enough to allow the other Sisters who began arriving from Pretoria, Johannesburg, Boksburg and Soweto to welcome me, “the American Sister.”

About halfway through the meal, four Italian priests of the Stigmatine Order also arrived to welcome “the American Sister.” They lived down the hill from us, our properties separated by a vegetable garden (often the site of baboon visits that left the fathers with few or no veggies!).

Evicted from China in 1949, the “Stigs” began ministering in South Africa in the 1960s: evangelizing, building churches, forming communities of faith and bringing joy in worship to the whole Ga-Rankuwa (Ha-Rankuwa) pastoral region. They built, trained and organized.

They also printed thousands of copies of A Re Rapeleng (Setswana for “Let Us Pray”). This little book — which fit comfortably in a pocket — was a treasure! The prayers of the Mass were in Setswana and English. There were hymns in Tswana, IsiZulu, Sotho, Venda, Tsonga and English, even a few in Latin.

Every Sunday, the Stigs produced a parish bulletin with announcements, words from the Holy Father, words from the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference, and/or stories of saints, all in Setswana.

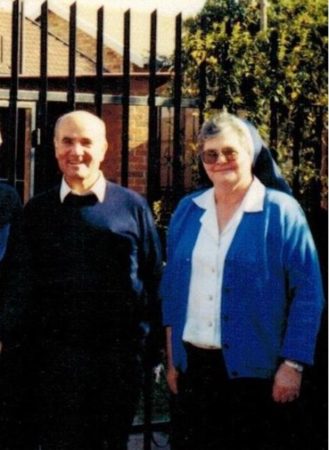

Father Michael and Sister Majella at the Soweto convent

Father Michael and Sister Majella at the Soweto convent

Father Michael, the barely 5 foot Italian dynamo whom the locals called “Masusumetsa” (“the Pusher”) was unstoppable. When he advocated for municipal water and electricity for the village of Mmakau, (and was briefly detained by authorities for his efforts), eventually, village households enjoyed water and light. When he asked the Mercy superior in Johannesburg for Sisters to staff the new high school, Tsogo (Resurrection), he kept asking until he got a yes.

One of Father Michael’s favorite building projects was the 90 room retreat and conference centre: Christ the New Man. Of course, the name bugged me from the start. “Why isn’t it Christ the New Person?” the “cheeky” American demanded.

The centre offered hospitality to everyone, including black Africans (not welcome in whites-only centers). The Stigs created places of welcome and freedom where Africans who had been forcibly removed from their homes and property could experience in the church their own agency and human dignity.

At the end of the meal that night Father Ugo, wig on his bald head and accordion in hand, led us in his version of an Italian opera chorus: “It is so wonderful to be together! Love, peace and happiness wish one another!” This was a moment of the “known unknown,” a new place, unfamiliar faces, and the mystery of two communities living the founders’ dreams miles and years into the future.

Was this the disciples’ experience after the resurrection of Jesus? Something familiar about the stranger in the room? Something familiar about the way each one laughed and joked, listened and sang?

[Jean Evans is a Sister of Mercy from California who ministered for 28 years in South Africa, where she worked in Johannesburg with victims of the apartheid regime. Back in the US, she is currently doing vocation ministry, substitute teaching, spiritual direction and grant writing.]

This article was first published in the Global Sisters Report on 3rd December 2019 and was written by Jean Evans rsm